- English

- Français

Abdelhak Kamal est Professeur Habilité en Economie à la Faculté d'Economie et de Gestion de l'Université Hassan 1er. Il est titulaire d'un Ph.D. en Économie à l'Université de Toulon et d’un Master recherche en Économie Spatiale à l'Université d'Aix-Marseille. Il est Qua...

Voir l'auteur ...Though the UN defines all those aged between 15 and 24 as young people, in Morocco the transition to adult age is not complete until the age of 29 (Ministry of Youth and Sports, 2001; World Bank, 2012). Indeed, 87.5% of those aged between 15 and 24 are unmarried, 81% live with their parents and 65% are inactive (HCP, 2012). Within “youth” as a group many diverging paths are taken but it remains a category with common problems, and for whom the situation is particularly worrying (unemployment, poverty, exclusion, vulnerability, weak participation, etc.).

Unemployment and social injustice were among the main drivers of the ‘Arab Spring’ since 2011. Employment is an important element of social justice as it provides a sense of inclusion and belonging. Unemployment is not simply a matter of not having a job; it draws in its wake a whole set of supplementary difficulties and can have large-scale social consequences. This is why promotion of full, productive and decent employment must be at the heart of economic policy. In fact, inclusive growth must ensure that all people reap the benefits of growth. In particular, it must generate more and better jobs, especially for the most vulnerable population, women and young people, affected or threatened by poverty and social exclusion.

Employment and social policies in Morocco appear to have failed to overcome social inequalities and correct the imbalances that cause youth unemployment. Informal work, precarious working conditions and lack of social protection continue to affect the majority of the Moroccan youth. The jobs young people do are often precarious, poorly paid and do not benefit from social protection (HCP, 2012; SAHWA Youth Survey, 2016).

Various policies have been adopted to address youth issue. The aim of this paper is to present the current state of youth policies in Morocco in order to subsequently observe the way these policies can contribute to improving young people’s situation by drawing lessons from their effectiveness and the challenges to be faced.

Early drop-out from the education system is one of the major hindrances to the development of human capital in Morocco. A large proportion of young people leave the education system without any qualification. School dropouts hamper the generalisation of compulsory education. Of pupils enrolled in the first year of public primary education, only 35% manage to complete this cycle without repeating, 18% finish high school, 6% reach the end of upper secondary school and pass and only 3% receive the baccalaureate2. According to the results of the SAHWA Youth Survey, among those who had left school, 26% of young people said it was due to their inability to overcome the difficulties of learning, 11% the need to work and help their family (of whom 3/4 were boys) and 10% to prepare for marriage (of whom 90% were girls). 43% did not foresee returning to school even if the opportunity was offered to them. The level of illiteracy is relatively lower among 15–24-year-olds. The national level fell from 29% to 11%3 between 2004 and 2014 thanks, notably, to the progress achieved and the efforts made on the generalisation of schooling during that decade.

Private education in Morocco seems to be a response to steadily growing demand and major concerns among families about school failure and access to quality education (the proportion of private schooling has reached 11.3 in 2013 with a growth rate of 9.5% per year) . This significant growth of the private sector can be called into question with regard to public education, as well as the impact in terms of equal opportunities and the right to quality education for all. The results of the SAHWA Youth Survey show that the chances of inclusion are higher for young people who have studied in the private sector. The level of professional integration is 37% for young people who4 studied exclusively in the public sector. It is around 52% for those who studied at least partly in the private sector and 62% for those educated entirely in the private sector.

According to SAHWA Survey data, 39% of young people aged 15 to 29 are on the labour market (40% of them are employed and 60% unemployed). Young people’s employment is characterised by great precariousness and serious fragility. According to the SAHWA Youth Survey results of 73.3% of active 15–29-year-olds are not registered to any system of medical coverage and work without a contract. Only 21% of active young people are permanent employees, 33% are self-employed and 27.6% are temporary staff. 80% of those are working without contracts or with a fixed-term contract. In terms of pay, 82% of active young people earn salaries of under 3000 Dh, while 93% of young women earn less than that. The analysis by gender reveals pay inequalities to the detriment of women.

The family continues to play a central role and is often a substitute for public policies, notably in terms of housing (most young people still live in the family home), finding work and funding projects, etc. The analysis of the means of acquiring a job shows that 63% of employed young people used personal and family relations to secure their job, with the exception of those with a higher level of education (50% have used regular channels such as job boards). When it comes to entrepreneurship, 61% of young entrepreneurs are financially supported by their parents. Lack of information (44%) and commercialisation (30%) are the major constraints on the development of entrepreneurship. This raises questions about the effectiveness of the mechanisms of intermediation for professional integration and state’s aid for the creation of enterprises.

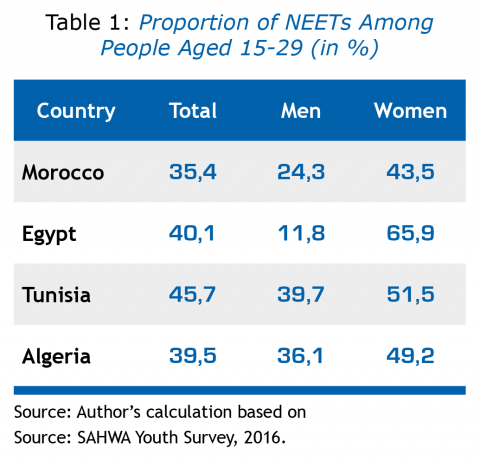

The growing number of young people who are neither working nor in education or training (‘NEETs’) is a particularly worrying problem with regard to their employability. NEETs receive little attention in most employment policies. Table 5.2 provides estimates of their numbers in selected countries, based on data from the SAHWA project5. Within the 15-29 age group the proportion of NEETs is around 35 per cent for Morocco, 39 per cent for Algeria, 40 per cent for Egypt and 46 per cent for Tunisia. Rates are much higher for young women (Table 1). This exclusion of young people from the labour market contributes to maintaining high levels of poverty. Weak prospects of finding work breed discouragement, which in turn could itself become a cause of inactivity.

The situation of young people in Morocco is a subject with multiple problematics and over arching issues. That is why it has recently formed a public action group6. Awareness has been growing over the past decade of the need to take young people’s needs and expectations into consideration when designing public policies.

The need for a suitable policy dedicated to young people was expressed in Morocco in the 1990s through the setting up of the National Council for Youth and the Future, whose main mission is essentially to inform public decisions on the situation of young people. Several reforms have been made since then, mainly in order to remedy the problematic of youth unemployment and favour their social inclusion. Mechanisms centred above all on the issue of employment and the professional integration of young people. The findings are unanimous (Rapport du ConseilEconomique et Social, 2011): despite the efforts deployed, the instruments have only reached a very limited number of unemployed young people and the results remained warfed by the extent of youth unemployment.

These programmes have had no impact on certain groups of young people who are hit hard by unemployment, in particular, young dropouts falling out of the education, the long-term unemployed and young people with specific needs. The quality of the jobs created is one of the weaknesses attributed to these programmes. The Idmaj programme’s entry to the work force contracts does not envisage social security coverage for the beneficiaries, which makes the measure unattractive.

Awareness of the youth problematic is shown by a series of intervention measures that is nevertheless operated to the detriment of the coherence of the policies put in place in this domain. Over the past decade, the situation of young people in Morocco has been recognised as a priority challenge that demands decisive, appropriate policy responses.

These days, young people’s place in public policy, in the sense of policies envisaged for their inclusion and their social protection, ranks as a priority. The new National Employment Strategy 2015-2025, the National Strategy for Vocational Training 2021 and the National Integrated Youth Policy 2015-2030 are initiatives based on a global focus that aims to grasp the set of problems young people face and understand the complexity of their contemporary reality and the issues that relate to them. Among the targets set, greater involvement of young people in the conception of public policies is sought, along with a reduction in inequalities and the economic and social inclusion of all young people in Morocco so that they can benefit from the same opportunities.

The effectiveness of the new national strategy is dependent on the involvement of young people not only in the development of policies, but in their implementation and follow-up so that the programmes envisaged have a real impact on their conditions. It must also lead to a decentralisation of these provisions so that they are entirely appropriate by local authorities. They are able to mobilise actors, associations and enterprises at local level and translate the strategic guidelines into instruments that genuinely guide young people towards professional inclusion and the realisation of their projects.

It is clear that the higher levels of youth unemployment and precarious working conditions have contributed to youth poverty and social exclusion, inhibiting young people’s autonomy and impeding their personal development and general well-being. The situation is even more concerning when it comes to young people without qualifications because of the difficulties encountered not only in the phase of transition towards adult age, but because it has repercussions on their whole life. The ever-growing proportion of young people who are not in school, employment or training requires often very expensive measures to be taken. But this is largely offset by the positive effects in the long term on the whole of society in terms of employment, social cohesion and security, among other benefits.

Employment policies for young people must be supported by mechanisms of social protection specifically aimed at them. The improvement of the integration of young people must be conceived as a collective responsibility that requires the involvement of all actors (public powers, social partners and youth organisations). Indeed, youth organisations must always be considered partners in the implementation of the policies that relate to them. Young people must not only participate in the development of policies, they must also be constantly involved in their implementation and their follow-up so that these projects have a real impact on their conditions

References

Notes